Gothic Christmas: A Deep Dive into Victorian Christmas Tales and a Moody Yuletide Playlist

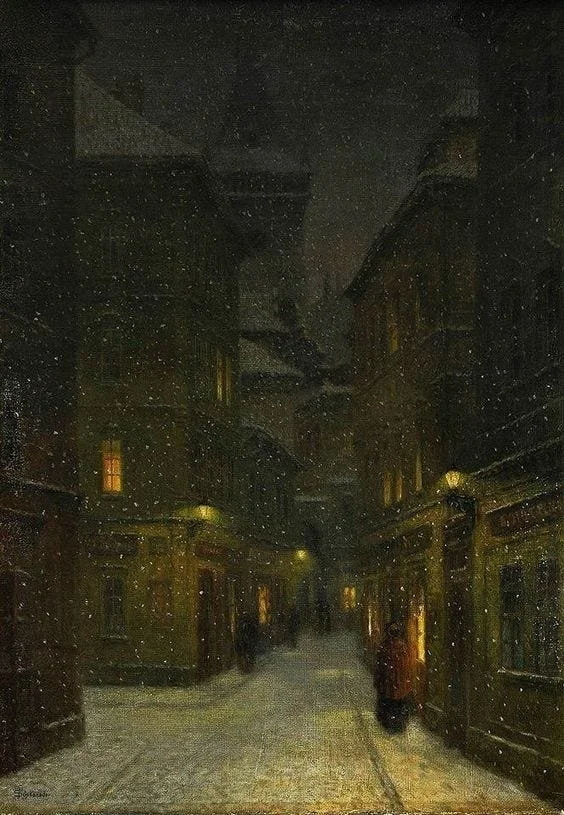

Woman in Falling Snow, Nicolai Malicheff (fl. 19th century)

There is a darkness that lurks within the pages of Victorian Christmas tales- an underbelly of festivity that paints a picture of coldness, long snowy nights and shadowy candlelit rooms. Peculiar characters are situated in desolate worlds, isolated by downpours of rain or thick sheets of snow. As the days slip into early darkness, streets are consumed by ominous blue-black light, a light which conceals unseen creatures and supernatural presences as they blow cooly into the corners and cracks of homes.

In the Victorian era, Christmas was often used as a time to reflect on the boundaries between the living and the dead. Many aspects of the Pagan holiday of Yule were subsumed into Christmas during this time. Yule, which has roots in Nordic and Germanic regions, centres around the Midwinter Solstice- the darkest day of the year. Festivities placed an emphasis on the consumption of meat, an honouring of light and the regenerative abilities of the sun, and a celebration of the year’s harvest. As these traditions bled into the Christian holiday which marked the birth of Jesus Christ, the period of Christmas was recognised as a holy day where both light and dark supernatural presences were particularly potent.

Otto Hesselbom, Christmas Eve at the Grave, 1896

The nature of the holiday being situated in the depths of Wintertime meant that people were more likely to fall into sickness, and therefore the presence of the other side loomed closely. Ghost stories were often told fireside during Christmas time as a way to feel a rush of warmth and connection during the darkest nights of the year. The harsh climate was also thought to conceal spectral energies within its zephyrs, that seemed more likely this time of year to play tricks on already weary minds.

Henry Mosler, "Christmas Morning", 1916

Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1848 story, Christmas Storms and Sunshine contains classic emblems of a traditional Christmas Gothic: the sickly child, the cold Winter, an atmosphere of disdain and tensity, and of course, a Christmas feast. It tells the story of two couples, the Hodgsons and the Jenkins’s, who happen to live in the same apartment complex, but whose husbands both work for opposing newspapers that criticise the other regularly. Though the wives of the family are insistent that they remain enemies, forces larger than them bring them together on Christmas Day, including a sudden croup sickness that falls upon the Hodgson baby, almost killing her. In her desperation Mrs Hodgson asks Mrs Jenkins for help, and despite the fact that she was beating Mrs Jenkins’ cat for stealing their food, Mrs Jenkins complies. On Christmas day, the baby makes a miraculous recovery and the two families share a feast together. Despite the happy ending, the story dips in and out of momentary frightfulness through descriptions of ghost-like humans and a dreary, unsettling atmosphere.

“It was the day before Christmas; such a cold east wind! such an inky sky! such a blue-black look in people's faces, as they were driven out more than usual, to complete their purchases for the next day's festival.”

Another emblem of the story is fire, which is described as a life force. It is the low fire that makes the baby sicker, warmth that brings her back to life, and a blazing fire that heats the food for their feast.

Mary Louise Fairchild "Christmas Eve in the Studio" 1911

Fires are representative of pockets of light in the midst of inescapable darkness. They are a symbol of hope that one day the sun might return to melt the harsh Winter snow, revive the frozen-over crops, and breath life back into a period of isolation. Hans Christian Andersen uses the same symbolism in his 1845 text, The Little Match Girl. In this story, a little girl wanders aimlessly through empty, snow-covered streets at night. Her shoes are nowhere to be found, nor are her parents or any sign of where she might have come from. Against a wall, the little girl lights a match, and within the flames, she sees different microcosmic dreamworlds that mesmerise her until they expire. In the flames she sees a spread of food, a bright Christmas tree, and the face of her dead grandmother.

“A second was rubbed against the wall. It burned up and when the light fell upon the wall it became transparent like a thin veil, and she could see through it into the room. On the table a snow-white cloth was spread; upon it stood a shining dinner service; the roast goose smoked gloriously, stuffed with apples and dried plums”

William Ewart Lockhart, Old Father Christmas, 19th Century

The story ends tragically. As she sees the face of her grandmother emerging wistfully from the flames of the match, the girl wants nothing but to be by her side. She wants to be within the flame, where she is contained alongside all the glorious food and the blazing tree lights. She continues lighting matches until they burn so bright that her grandmother takes her up into the light, above earth and with God. The little girl freezes to death beside the wall with a smile on her face.

“And the matches burned with such a glow that it became brighter than in the middle of the day; grandmother had never been so large and so beautiful. She took the little girl in her arms, and both flew in brightness and joy above the earth…But in the corner, leaning against the wall, sat the poor girl with red cheeks and smiling mouth, frozen to death on the last evening of the old year.”

The story, though bleak and melancholic, describes an illusive magic that blurs the veil between living and non living. Perhaps that is the true magic of Christmas- divine realms reached through the ignition of a flame, the undying will of childlike imagination, and the everlasting belief that heavenly spirits move through our dominions every single day. In Algernon Blackwood’s 1906 story, Keeping His Promise, Blackwood depicts the enchantment of a past companion as a harrowing, yet comforting experience. His protagonist (Marriott) is a university student in Edinburgh who is weary with study. One night, he receives a knock at his door and opens it to find a childhood friend that he hasn’t spoken to in years (Field). He looks thin and talks very little, but when Marriott takes him for dinner, he stuffs in the food as if he’s starving.

“He looked up and caught his guest's eyes directed straight upon his own. An involuntary shudder ran through him from head to foot. The face opposite him was deadly white and wore a dreadful expression of pain and mental suffering.”

They go to sleep and when Marriott wakes up, he sees that Field is nowhere to be found. However, he can still hear his breathing coming from different corners of the house. Stressed, Marriott turns to some friends to help make sense of the situation, wondering if he hallucinated the whole thing. He reflects on a scar from a pact that he made with Field when they were kids, in which they promised to visit each other first when they died. Marriott calls home and finds Field was found dead the same night he came to visit him.

Jakub Schikaneder, Street in the Evening, Prague, 1875

Against a backdrop of gloomy Edinburgh skies and misty grey cityscapes, Blackwood captures the unsettling unknowns hidden by the shadows of the night. There’s an anticipation during this time of year, that once forgotten memories will resurface, and visions of death will transform and come alive once more. He uses psychological confusion as a landscape for supernatural events to transpire, with the enchanting gloom of the Christmas season being a gateway into unreal realms. Perhaps Blackwood’s ghostly figure is representative of Santa Claus himself- a spirit that becomes real only to believers, a strange visit in the middle of the night, an unspoken message of peace, and an omniscient presence felt even when he’s not there.

“Haunted by visions of brain fever and insanity, Marriott put on his cap and macintosh and left the house. The morning air on Arthur's Seat would blow the cobwebs from his brain; the scent of the heather, and above all, the sight of the sea. He roamed over the wet slopes above Holyrood for a couple of hours, and did not return until the exercise had shaken some of the horror out of his bones, and given him a ravening appetite into the bargain.”

There is magic all around us all the time. During Christmas season, when we retreat into rest and isolation, the murmurs of magic find new avenues to reach us through. At Christmas time, we are all vulnerable to the hauntings whispers of the cold, dark night. As we close off of the year, we bring fourth a hibernation that regenerates both landscapes and people for a new year to come. It’s in this quiet period that we are forced to listen more. As a gift from me to you, I want to share a compilation of my favourite atmospheric Yuletide songs, to play in dimly lit rooms by a fire, or in a pair of headphones as you walk through a snowy city centre. You can listen to it via the link here.

Edmund Dulac, illustration from “The Snow Queen” in Stories from Hans Andersen with illustrations by Edmund Dulac, 1911